Sheet Metal fabrication techniques don’t change very often, but that doesn’t mean innovation is completely absent. Let’s look at some ways bending has changed over the last century.

Relative to some other industries, sheet metal bending really isn’t all that old. Manufacturing and production using sheet metal components largely took off in the late 19th century during the Industrial Revolution. Using the newly developed concept of the assembly line and machines like press brakes, fabricators could produce more parts in higher quantities. As the market grew, so did profit – the element that so often precedes innovation.

Three primary techniques were used to bend sheet metal: Bottoming, Coining, and more recently, Air Bending (ca. 1970-1980). Each technique is defined largely by the design and use of the tooling associated it.

Coining – When using the coining technique, fabricators would use a matching punch and die set, similar to bottoming. The force of the bend operation is what truly sets coining apart, however; compared to air bending, coining presses the sheet into the lower tooling anywhere between 5 to 30 times harder. The sheet ends up being thinner at the bend point and is deformed as a result. There is essentially no springback, but the material is compromised.

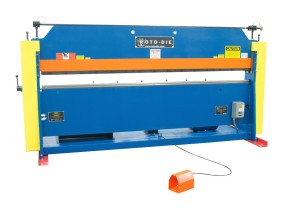

Many modern benders, like the one pictured here, are designed to operate using the air bending technique.

Bottoming – A bend radius is forced by pressing a punch into a v-shaped die. The dies are commonly set at 90 degree angles, since it is the most common angle used. Punches were typically 90 degrees, as well. Bottoming was favored for its accuracy and minimal springback, but often slowed production because changing angle or material gauge requirements meant swapping out the correct match of upper and lower tooling.

Air Bending – Although a variation of air bending was used for obtuse-angled bends in the past, it was formally developed as a technique in the 1970s. When pressing using air bending, the operation usually requires less force and thus smaller tooling can accomplish the same job as a more forceful bend, like coining. Special attention must be paid to stroke depth since the sheet is not pressed all the way into the die, but this same characteristic means that air bending accommodates some level of flexibility in forming different profiles. Perhaps the biggest differentiator between air bending and the other bend techniques, however, is that upper and lower tooling do not need matching radii. Instead, malleability of the material will determine the bend radius.

Because of the flexibility with tool usage, some press brakes have made swapping out the lower tooling easier for operators. Roto-Die hydraulic benders use a cylindrical die notched with different angles, and operators need only turn a lever when switching between jobs. The pairing of machine design with air bending technique helps maximize production output for fabricators.

Do you have a prediction on what’s next for metal forming? Tell us in the comments!